Looking back I can see more effects here than I was aware of at the time. The question of diet carried over from school, as although in the beginning our ration books were changed from vegetarian to meat-eating at the start of the school holidays, and then back again, this was eventually found to be unmanageable, and we had to have vegetarian books all the time. This was tough on our parents, who shared their meat ration with us, but our veggie ration books gave us access to additional cheese and eggs, and more in the way of nuts and dried fruit than was available to everybody. I remember too a delicious cashew nut butter known as Nutter, which made a really tasty spread.

My father was running a small-holding of vegetable garden and fruit orchard, and I remember that because of gathering the fruit harvest, we always had to take our holiday in September. Somehow it always seems to have been lovely weather, though, so we did not mind. And my mother kept hens and geese, so in fact we had a pretty good diet both at home and at school. I remember that the feeding of the hens and geese required the saving of all food waste to be boiled up as swill, a foul-smelling concoction which drove us out of doors when it was cooking on the stove. [Here my Dad is up a tree picking apples.]

My father was running a small-holding of vegetable garden and fruit orchard, and I remember that because of gathering the fruit harvest, we always had to take our holiday in September. Somehow it always seems to have been lovely weather, though, so we did not mind. And my mother kept hens and geese, so in fact we had a pretty good diet both at home and at school. I remember that the feeding of the hens and geese required the saving of all food waste to be boiled up as swill, a foul-smelling concoction which drove us out of doors when it was cooking on the stove. [Here my Dad is up a tree picking apples.]

A rather posh neighbour of ours kept a Jersey cow on her lawn for a time, as her contribution to the war. She kindly offered to leave out two glasses of rich creamy milk in her lovely cool dairy, and my brother and I were expected to walk down the hill and back again to take advantage of this extra nourishment. I remember it being a rather boring obligation which we did not appreciate! However, it did not last long, as our neighbour was soon informed that all the product from her cow was expected to be handed over to the Milk Marketing Board for fair distribution – she was not supposed to give it away, only use what her own household needed.

As our land included a paddock and a large barn, we became a centre for the local salvage collection, mostly paper and scrap iron. I remember discovering a large Spanish dictionary in the paper waste, somewhat like Larousse Illustré, and insisted on keeping it, as I was doing an A-level in spanish. We still have it today, although it was already somewhat battered when it came to us.

My father had to put the car away in the garage, as there was no petrol to run it. We had a butcher and a baker and a Post Office and small store in the village, and the farm which delivered our milk was on our doorstep. Otherwise, there was a fortnightly bus into Worcester seven miles away for all other shopping. For us this involved a 10-15 minute walk down hill to the bus stop with empty bags, and then an uphill slog with bags loaded with a fortnight’s shopping on the way home. No wonder my mother had to have prolapse surgery in her 40s.

But there was also produce to be got to market, and for a while we ran a pony and trap, which we parked in the car park alongside whatever cars were there. The first pony we bought turned out to have been doped by the crooked dealer, and became unmanageable after getting home. My parents had no idea how to choose such an animal. The second buy, an amiable little Welsh pony called Mick, turned out fine, and my brother and I were able to ride him as well. [This is me up on Mick, with my brother leading him.]

I remember that on our shopping expeditions to the town we used to lunch at the British Restaurant. These were a sort of communal kitchen set up in schools and church halls by local authorities on a non-profit making basis, where one could get a good wholesome meal for about 1/6d (8p), without handing over food coupons. I remember too that in those days of shortages, teas and coffees in cafes and restaurants tended to be served with one lump of sugar for each perspm, and if one did not take sugar, one put it quickly in one’s pocket, and took it home for use in cooking, hopefully collecting those of other non-sugar-takers too!

I think the worst thing I suffered personally was the clothes I sometimes had to wear made over from my mother’s by a local dressmaker. I could tell that they were not stylish and they embarrased me. Only a few years ago I was using up a set of dusters which my mother had bought with a view to turning them into some sort of garment. Thank goodness that project was never realised. Incidentally, I still have one or two left of the black satinised cotton blackout curtains we used. These have been made up over the years into a variety of fancy dress costumes for school plays and local amateur dramatics.

For a period we gave houseroom to my father’s sister from London, together with some other London relatives. This was hell for my mother, with two other women in her kitchen. The other family lived in quite a different way from us, and I can remember our horror on one occasion when they had prepared a cauliflower cheese for our supper, and it had come to table absolutely full of aphis which had not been washed out before cooking. I am afraid we made a bad hand of having evacuees in the house, even family, and I feel a bit ashamed when I think of all those other families who had no choice about taking in strangers.

When we moved to the country in July 1939, our new house had no electricity. It was due to come to the village, (which consisted of only about 250 inhabitants then), at any time, but of course the whole thing was put on hold with the outbreak of war. This meant that my mother cooked on a paraffin stove, we used paraffin lamps and candles to light the house, and it was my father’s daily chore to pump up water by hand from our well into our tanks, as we did not have mains water either (or sewage!). My parents were always so scared that our well would run dry (which it never did) that we had to get used to using the loos but not flushing every time, a custom which our guests understandably found very distasteful!

Electricity did not in fact reach our village until 1948, just in time for my 21st birthday party in the November. So we had a double celebration that weekend with a house party, who enjoyed light and water ‘a gogo’, not to mention a lot of luxury foods such as a cooked ham and cream meringues, acquired by saving up coupons, or by gift, barter or exchange, at a time when food rationing was still in force. (My mother took eggs from our hens to the local Kardomah cafe, and they were very happy to bake the meringues for us because they were able to keep the egg yolks! I guess we had to save up lots of our sugar ration though.)

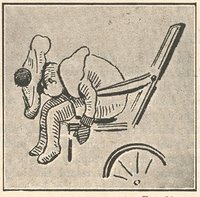

In the summer of 1940, when I was 12, I went to stay with my friend Julia, and her dog 'Hitler', who lived on a pig farm in the country – (oh! the stink!). On this particular day there was a whole crowd of small children, of which Julia and I were the eldest, playing some distance from the farmhouse, and an aunt was dispatched to bring us back in the car for lunch. Crazily, we all clambered up onto the running boards, bonnet and even roof of the car. Julia and I having the longest legs took the top position, facing forwards, with said legs presumably obscuring the driver’s view to some extent.

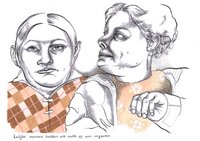

In the summer of 1940, when I was 12, I went to stay with my friend Julia, and her dog 'Hitler', who lived on a pig farm in the country – (oh! the stink!). On this particular day there was a whole crowd of small children, of which Julia and I were the eldest, playing some distance from the farmhouse, and an aunt was dispatched to bring us back in the car for lunch. Crazily, we all clambered up onto the running boards, bonnet and even roof of the car. Julia and I having the longest legs took the top position, facing forwards, with said legs presumably obscuring the driver’s view to some extent. The car had begun to roll slowly down the lane when the dog decided he wanted a ride too, and made a leap for the bonnet. Aunt braked violently, children shot forwards onto the ground, but poor Judith’s travel was interrupted by contact with the car mascot, a penetrative design which passed through a portion of her gluteus maximus and out again, narrowly missing the sciatic nerve. I managed to pull myself off while sensation was still numbed, and when we had all got safely and more circumspectly back to the farm, the local GP was sent for and I was stitched up, adequately though not elegantly. That has not mattered though, as my buttocks have never been much to write home about and I never wanted to flaunt them.

The car had begun to roll slowly down the lane when the dog decided he wanted a ride too, and made a leap for the bonnet. Aunt braked violently, children shot forwards onto the ground, but poor Judith’s travel was interrupted by contact with the car mascot, a penetrative design which passed through a portion of her gluteus maximus and out again, narrowly missing the sciatic nerve. I managed to pull myself off while sensation was still numbed, and when we had all got safely and more circumspectly back to the farm, the local GP was sent for and I was stitched up, adequately though not elegantly. That has not mattered though, as my buttocks have never been much to write home about and I never wanted to flaunt them.